India has, for the first time in history, declared that it will not have a power deficit this year. The country will have a surplus of 3.1% during peak hours and 1.1% during non-peak hours during 2016-17, latest data from the Central Electricity Authority shows.

- This is the first time that the country has declared a year of no shortage though many regions have had power surplus for shorter periods. In 2015-16, the peak hour deficit stood at -3.2% while non-peak hour deficit was at -2.1%. The deficit was as high as 13% about a decade ago.

Regional variations:

- Data shows that states in southern India will have surplus power to the tune of 3.3% after being power starved for almost a decade.

- Western India will have surplus electricity at 6.9%.

- Eastern region will have the maximum shortage of 10.3% and northeastern region at 8.3%.

- The northern states will have a deficit of 1.8% during the year.

Reasons behind surplus power:

- Highest ever conventional power capacity of 46,453 MW has been added during the last two years.

- About 11,000 MW of gas plants have been revived and coal shortages to power plants are removed.

- The government has launched revival scheme for distribution companies and many states have joined it.

What’s the issue now?

India now generates more power than it needs and has surplus power. And yet, the practical experience of Indians is that scheduled and unscheduled power cuts are the norm in cities, and the situation in most rural areas is worse. India lags far behind other countries in per capita consumption of power.

What’s causing this?

- While capacity addition has peaked, industrial and commercial offtake remains low. Growth in industrial and commercial consumption—the highest-paying segment under the telescopic tariff structure followed—was only around 4.57%. Only the domestic consumer segment, which puts additional cost burden on the distribution utilities given lower tariffs, saw decent demand growth of 8.9%.

- Cost of supply has increased, as have aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses. Domestic consumers do not have the capacity to absorb all the incremental power produced, or pay higher cost. Distribution companies, or discoms, typically incur higher cost on supplies to this segment and earn lower revenues.

- The state of the state-owned power distribution companies, or discoms, which are responsible for buying electricity from the generation companies and selling them to consumers, is also responsible for this. The discoms suffer massive transmission and distribution (T&D) losses. Almost 25% of the power is lost, and never gets billed for — double the global average of about 12%.

- Worse, the remaining 75% is sold at prices that are much lower than the discoms’ procurement costs. In every state, the tariff is set by a group of largely political appointees, who avoid increasing rates because of the associated political costs. Political unwillingness is at the heart of the T&D losses as well.

What’s the solution?

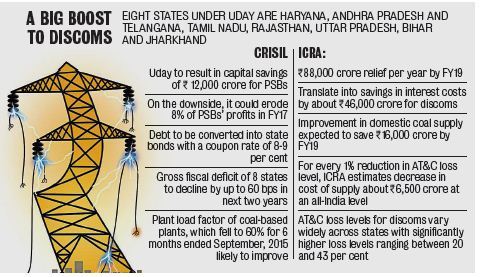

To help these discoms, government announced a new scheme — UDAY, or Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojna- in November 2015. Under UDAY, participating state governments would take over 75% of discom debt over two years — 50% in 2015-16 and 25% in 2016-17. The idea is to make the state governments formally responsible for the losses of state-owned discoms.

This is expected to have two effects. One, it will relieve debt-ridden discoms, who can push power distribution in right earnest instead of being a roadblock to economic growth. Two, the more overt acceptance of debts on their books will push states to align tariffs to costs, and make it possible for discoms to run on a sustainable basis.

Challenges before UDAY:

- Electricity is not a central subject, and states cannot be made to participate in the programme. Also, the Centre is not providing any monetary assistance. The Centre’s carrot, in this case, is actually its stick. As such, willing states will be provided subsidised funding from the central government’s power schemes, as well as priority in the supply of coal.

- State governments are expected to convert the discom debt into bonds. However, apart from the banks that had lent the money in the first place, finding buyers for such bonds might prove difficult — especially since these would not enjoy SLR status.

- Besides, there is nothing in the scheme to fix the perverse political incentive that leads to T&D losses and debts in the first place.

Way ahead:

The present surplus may not be adequate when industrial demand starts to pick up, or even to meet exigencies such as unscheduled generator shutdown or extreme weather event. Also, a truer, holistic gauge would be 24×7 reliable power supply to all at an affordable price.

- To achieve that objective, states will have to show strong resolve to reduce AT&C losses, invest in infrastructure development, ensure efficient commercial operation of discoms, make timely tariff revisions, and reduce the cross-subsidization that’s impacting the competitiveness of the industry and services sectors.

- The time is also right, perhaps, to provide direct, targeted subsidies to electricity consumers who can’t pay much—if at all. The learnings from the LPG direct subsidy transfer project would be very handy here.